Know when to diversify your management approach, and why

It’s 10:30pm on a Friday when my coworker Andy (not his real name) receives a text from his boss:

“Two weeks ago, you said X would be done today. Is it done yet?”

Andy has been working overtime every day for the past two weeks—but on a different project his manager reprioritized just after their original conversation.

Andy is a top-tier engineer: high velocity, highly technical, and brilliant. His boss is a middle manager with unrelenting standards who constantly pushes the team to deliver more. Both are doing exactly what their organizations expect from them, yet Andy was fuming and telling me he planned to quit the team.

Why? Because his manager was making two critical mistakes that I see repeatedly across the industry.

Mistake #1: Everything is Equally Important (But Nothing Actually Is)

A manager who insists everything must be treated with the highest priority while refusing to establish clear priorities among competing tasks is essentially asking for more output from the same resources. This approach will inevitably wear down your team’s energy and must be avoided at all costs.

I’ve seen this pitfall derail countless managers throughout my career. Here’s how to avoid it:

The Four-Step Priority Framework

1. Establish a visible plan. Use your scrum board, backlog, or status wiki—something that clearly documents your commitments to engineers about when features will be delivered.

2. Question urgency. When new work appears after your plan is set, ask “Why now?” Does this work need to happen immediately? If so, why?

3. Make trade-offs explicit. If new work is truly emergent, what gets dropped from your current plan? Always communicate the relative priority of new work when adding it to the plan.

4. Proactively communicate changes. Reprioritization affects future deliverables. Check how new work impacts your current plan and push dates out preemptively, then communicate these changes to your leadership.

Mistake #2: Fixing What Isn’t Broken

Not everything that goes wrong needs a management intervention. When exceptions happen, your job is to diagnose whether anything is actually broken and fix only what needs fixing.

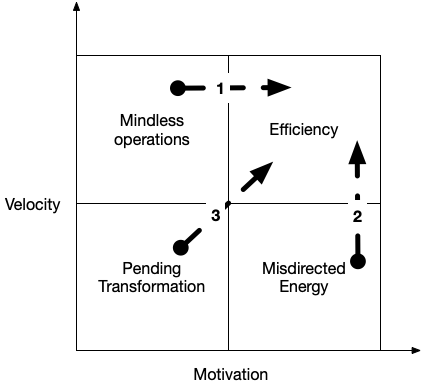

Think of engineer performance as a function of motivation and velocity, with your management approach as the transformation function. Your goal is to move everyone toward maximum efficiency, but first you must identify which state each engineer is in before taking action.

Figure 1: Output = F(Motivation, Velocity), where F is managerial influence

The Three States of Engineer Performance

1. Mindless Operations (High Velocity, Low Motivation)

A high-velocity engineer who’s losing daily motivation signals that work isn’t challenging or engaging enough. While the team might close lots of tickets and execute change management efficiently, impactful projects get delayed in favor of emergent issues.

This often results from a “Day 2” mentality, excessive tech debt with insufficient operational excellence focus, or an engineer who has outgrown their current challenges.

Your response: Sell the vision, boost morale, and make hard decisions. Consider dropping operational excellence work temporarily to focus on high-impact initiatives, or reprioritize the roadmap to complete existing features before starting new ones.

2. Misdirected Energy (High Motivation, Low Velocity)

This was Andy’s situation: highly motivated engineers working on the wrong tasks, leading to poor velocity. To address this, reflect on how you reached this state by asking:

- Have you clearly communicated the correct priorities? Are they blocked on something you can resolve?

- Have you provided adequate tools and resources?

- Is there a capability issue with the engineer?

As long as there’s no capability problem, it’s always better to course-correct and reflect on your management failures rather than asking accusatory questions disguised as inquiries.

3. Efficiency (High Motivation, High Velocity)

This is your target state. Maintain it through consistent practices that support both dimensions.

Building Team Efficiency: Four Key Practices

1. Foster open communication. Create an environment where no question is considered stupid and everyone feels comfortable speaking up.

2. Invest in growth. Sign people up for training, suggest relevant conferences, and organize team travel to spark conversations and inspire collaboration.

3. Celebrate regularly. Mark everything from team birthdays to feature launches. Recognition drives motivation.

4. Practice reflective leadership. In 1:1s, ask “What have I made more confusing recently?” This question surfaces issues before they become problems.

The Bottom Line

The title “Don’t motivate the highly motivated” doesn’t mean you should ignore your high performers. Instead, it means recognizing that different engineers need different types of support at different times.

Highly motivated engineers with low velocity need better direction and resources, not motivation. High-velocity engineers with low motivation need more engaging challenges, not efficiency pressure.

Your job as a manager isn’t to apply the same approach to everyone—it’s to diagnose each situation accurately and respond appropriately. When you do this well, you keep talented engineers like Andy engaged and productive instead of driving them toward the exit.

Comments